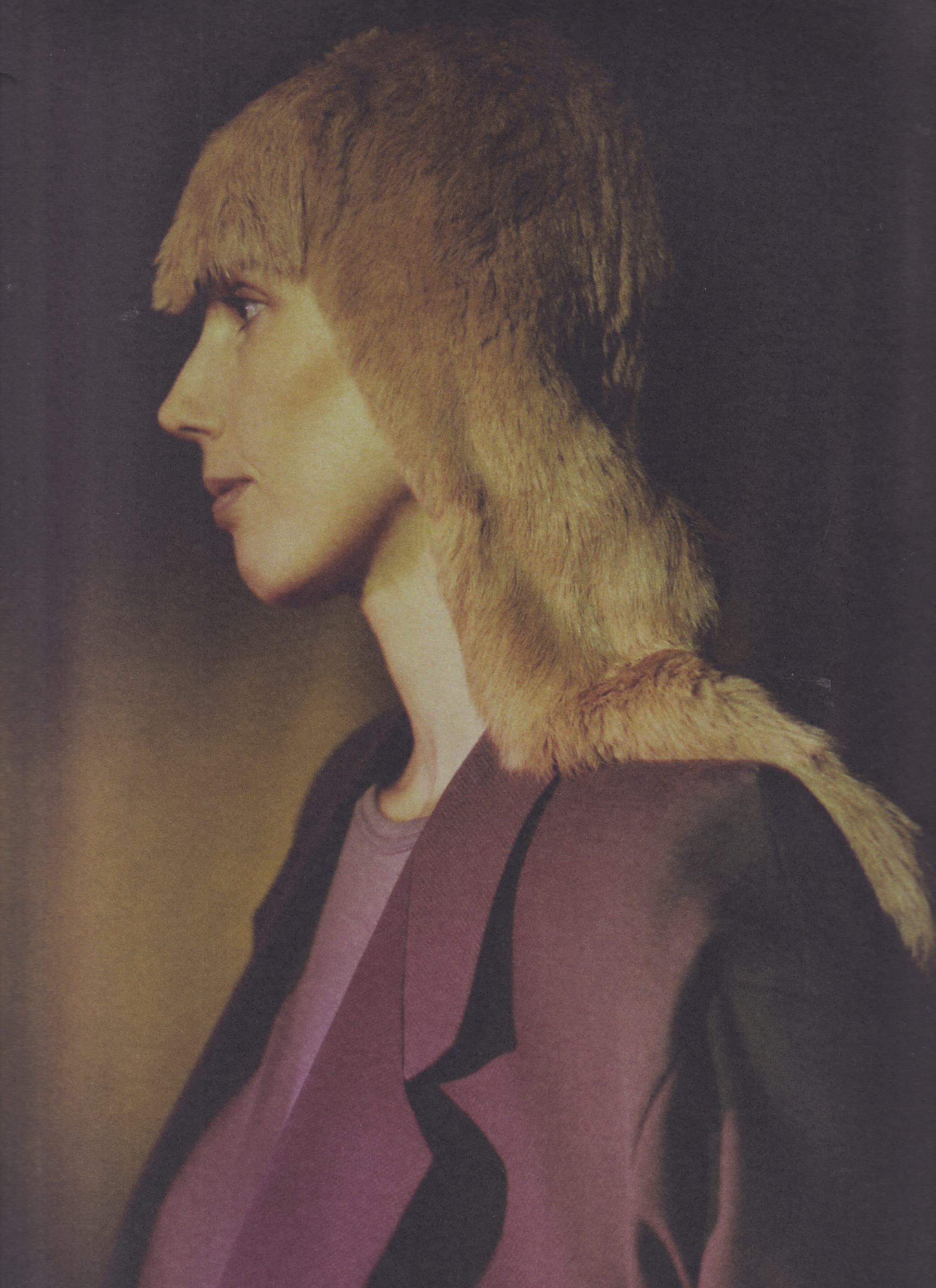

MAISON MARTIN MARGIELA X BLESS FUR WIG COLLABORATION, FALL/WINTER 1997

11/20/2025

Author: Soukita

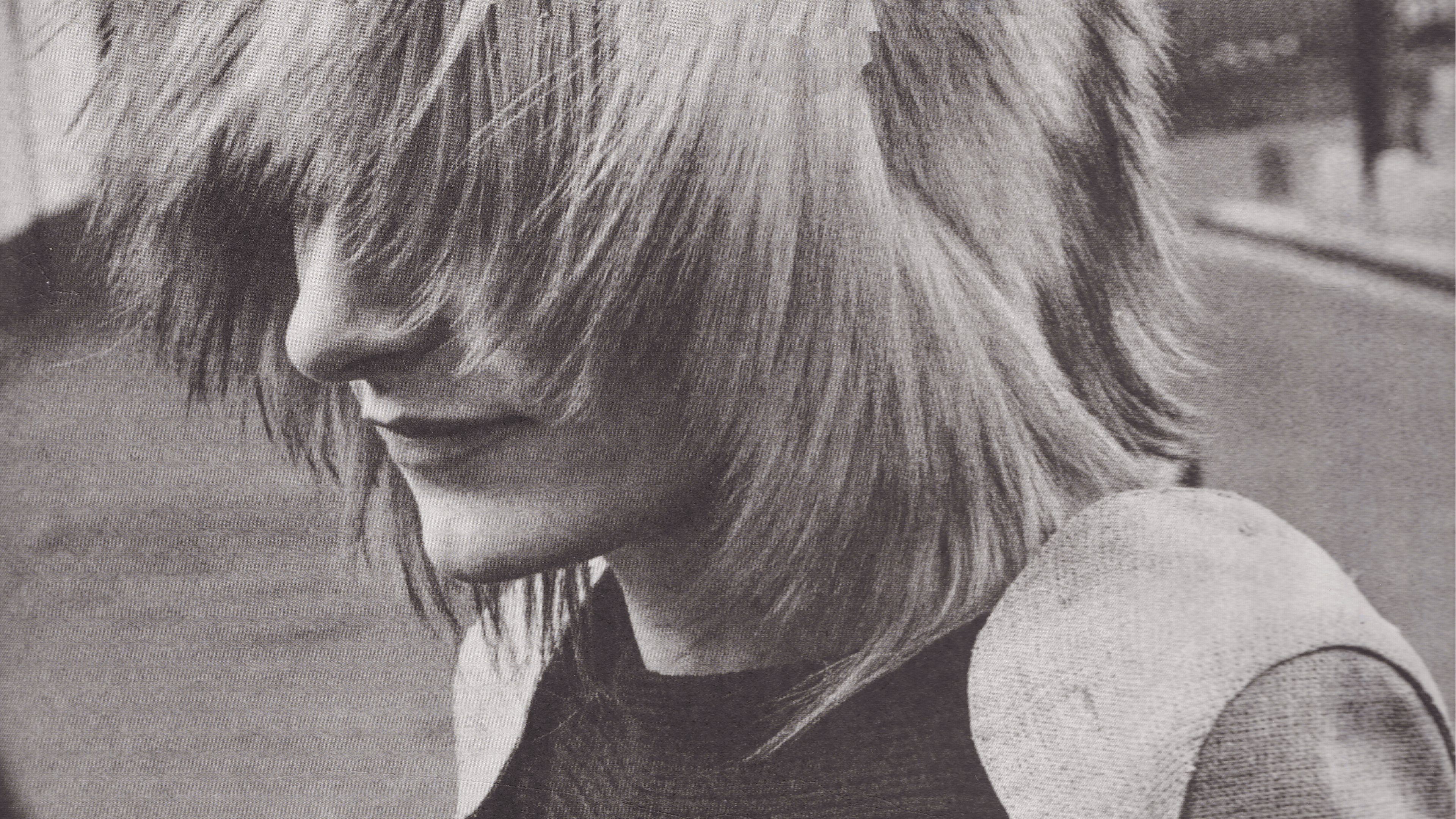

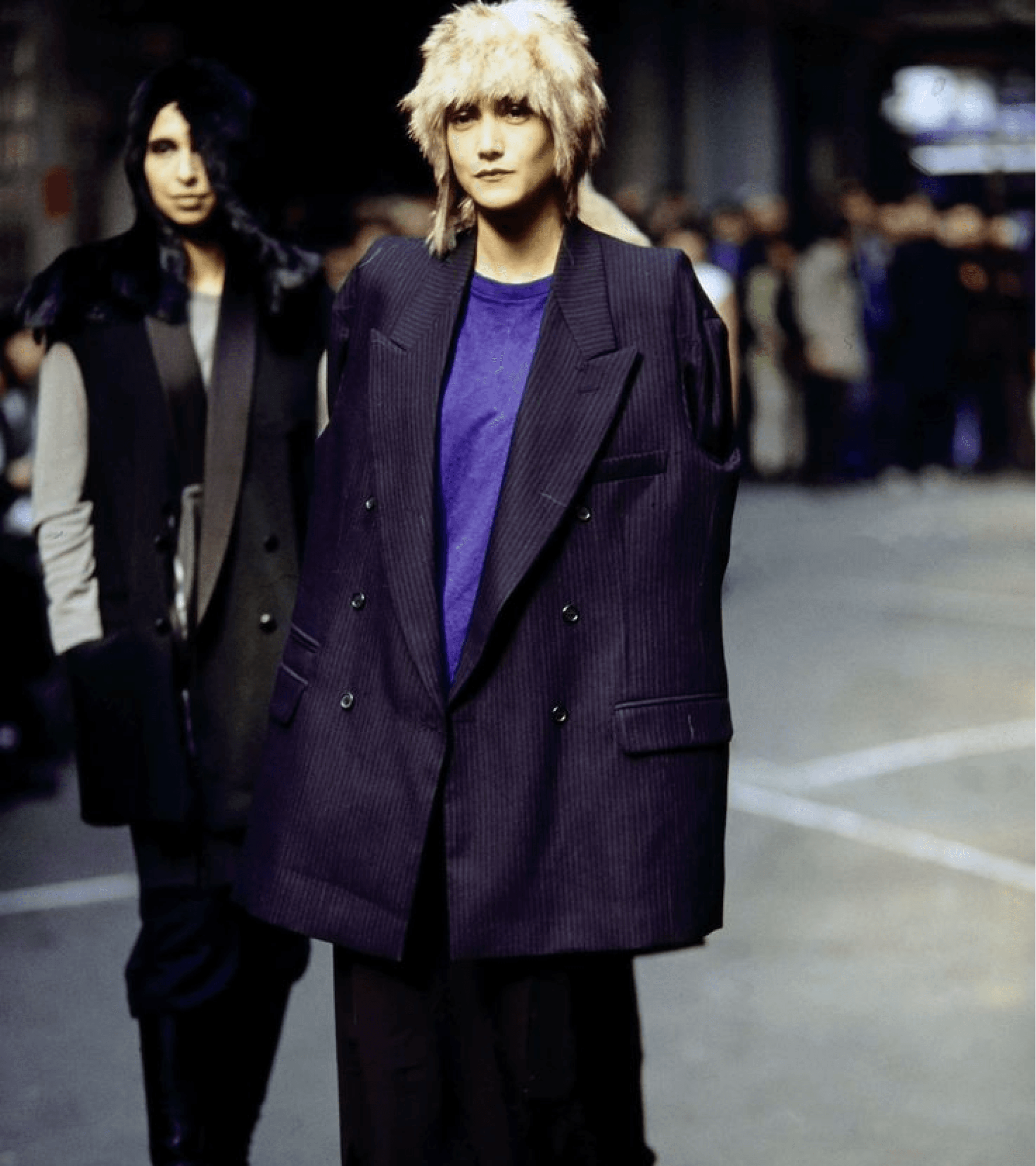

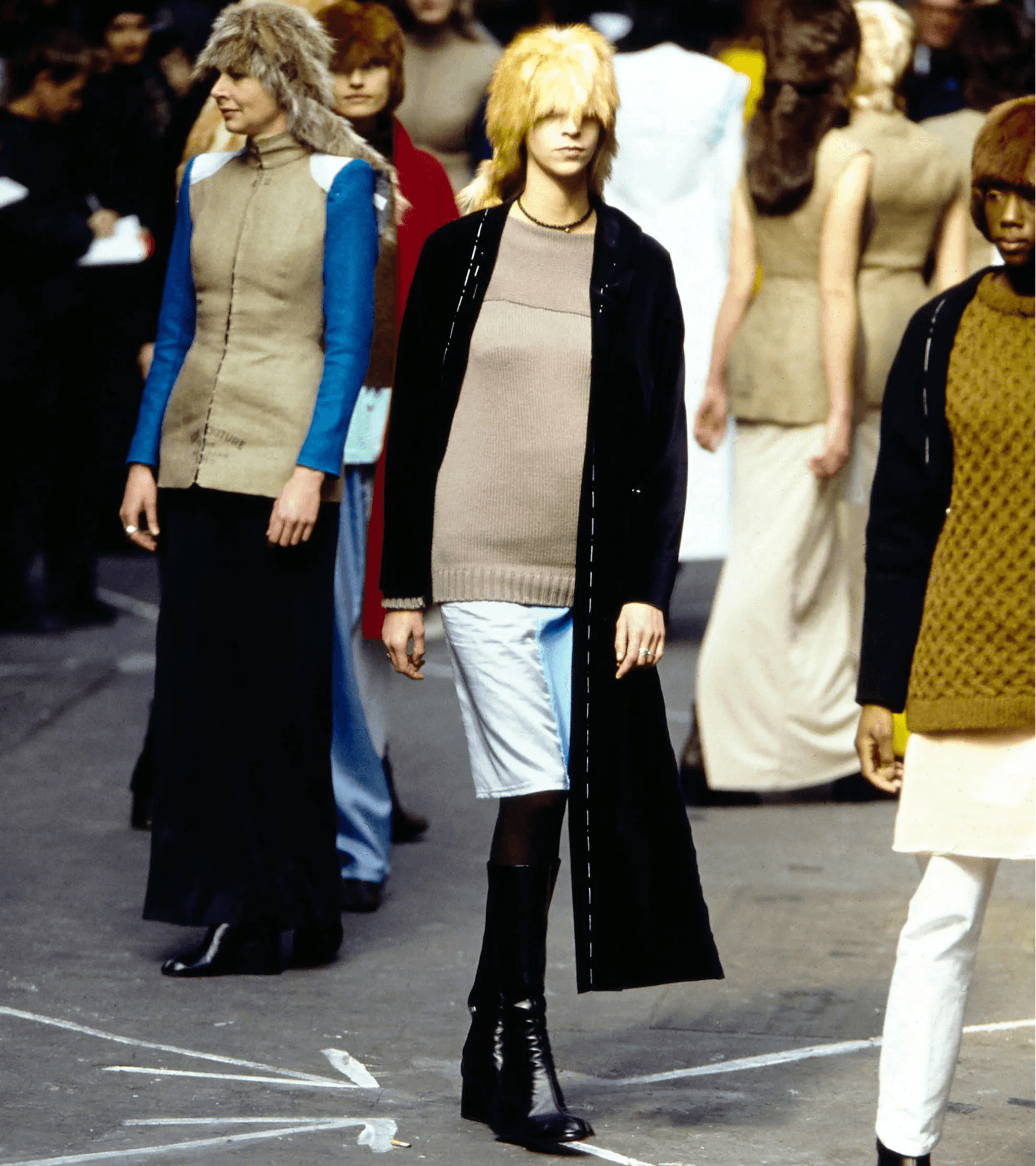

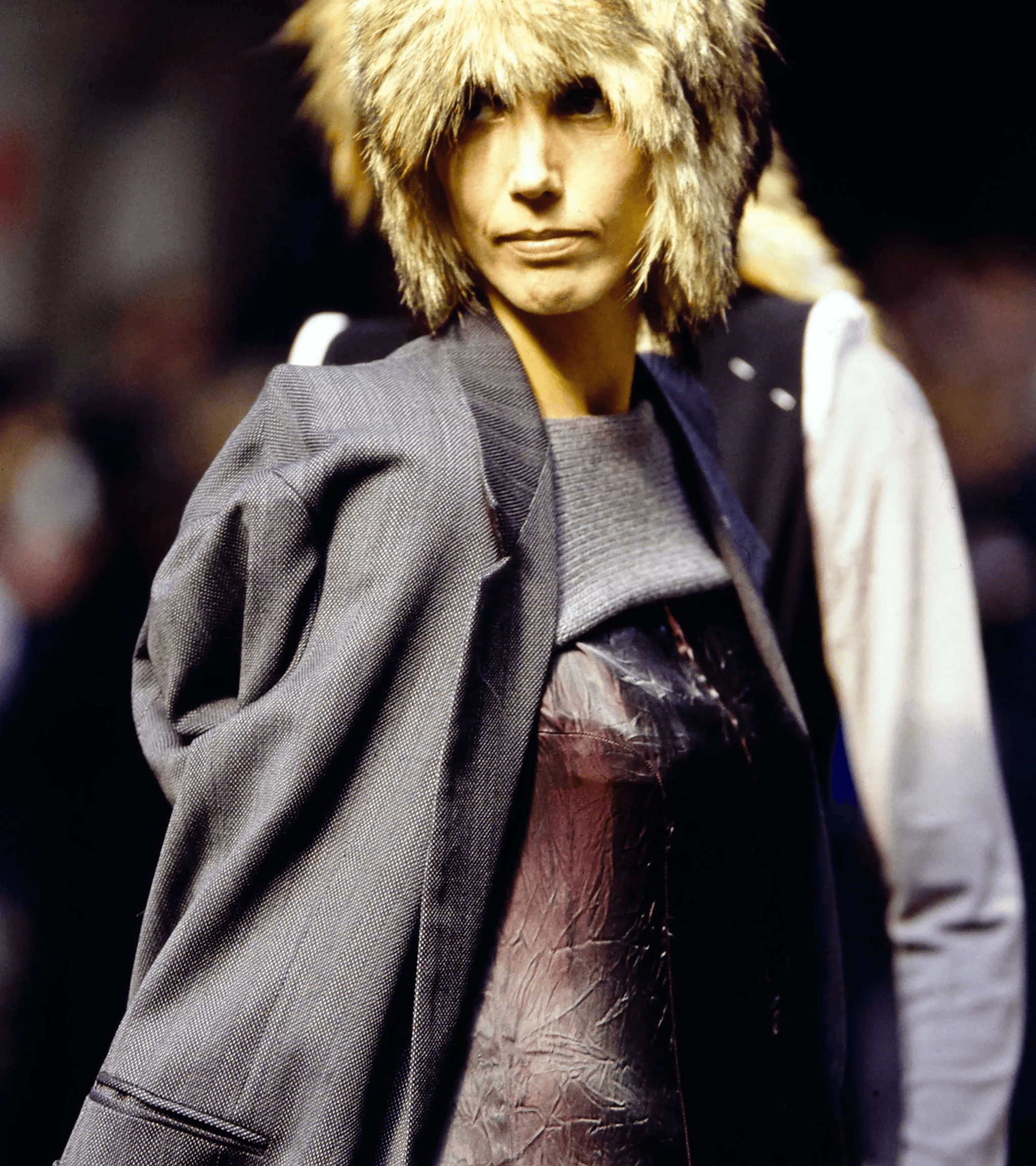

At the Maison Martin Margiela Fall/Winter 1997 ready-to-wear show in Paris, every model appeared on the runway wearing a wig constructed from real fur. These pieces, made from repurposed fox and rabbit pelts, were shaped to resemble common hairstyles such as blunt bobs and mullets, based on sketches by Martin Margiela. Their use corresponded with the house’s practice of incorporating found materials into garment construction. The same collection included garments made from brown pattern paper, coats with visible basting stitches, and asymmetrical pieces that exposed standard elements of tailoring. The wigs were produced by the design duo BLESS, whose work was included by invitation for the season’s presentation.

Maison Martin Margiela, founded in 1988 by Belgian designer Martin Margiela, had by the late 1990s become associated with practices such as enlarging miniature garments to human scale, printing photographic details onto textiles, and converting utilitarian or discarded objects into wearable items. The French press referred to this approach as “la mode Destroy.” The house frequently exposed structural features of clothing and altered standard construction techniques, positioning the Fall/Winter 1997 show within an already established vocabulary of deconstruction and reuse.

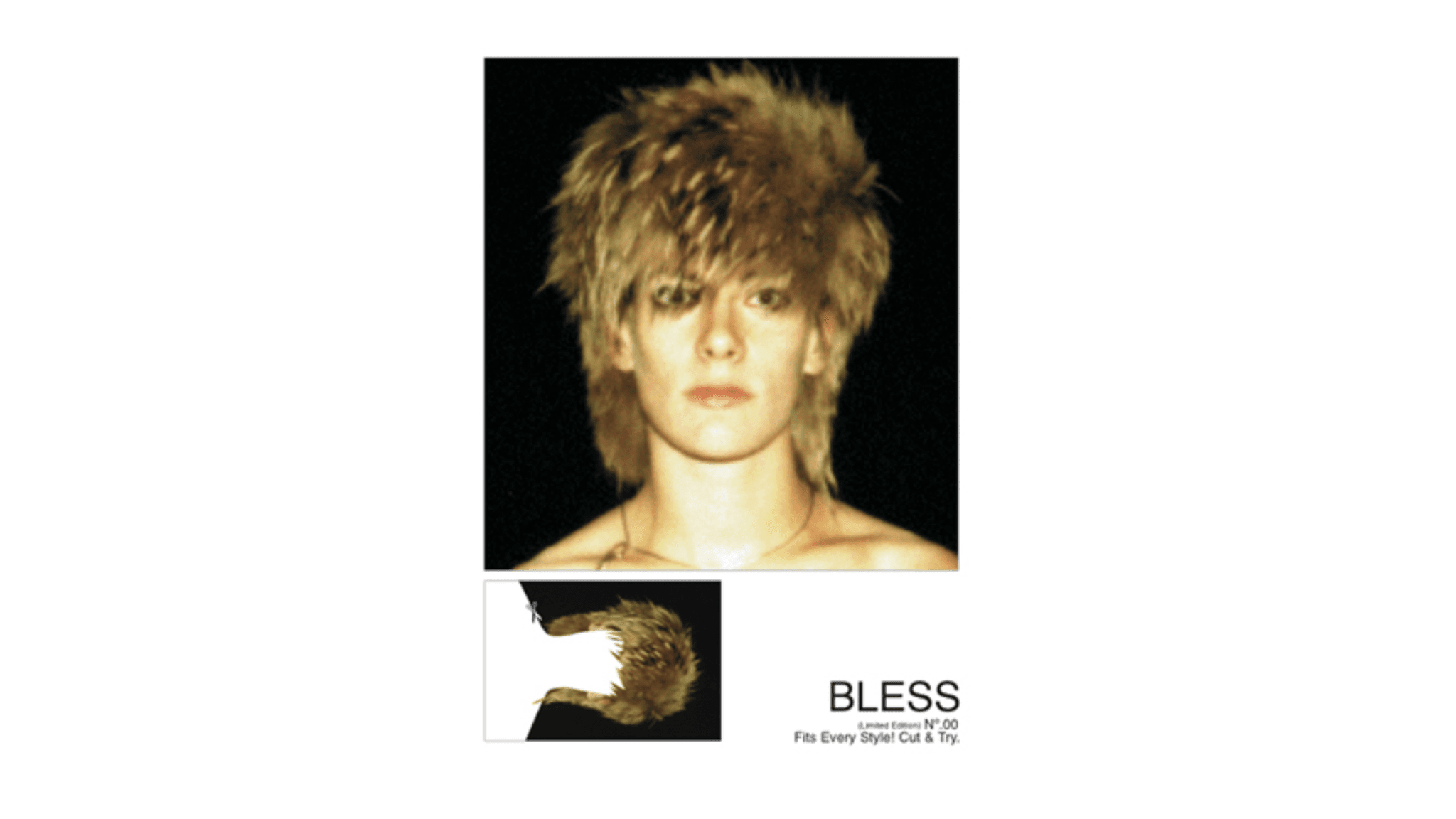

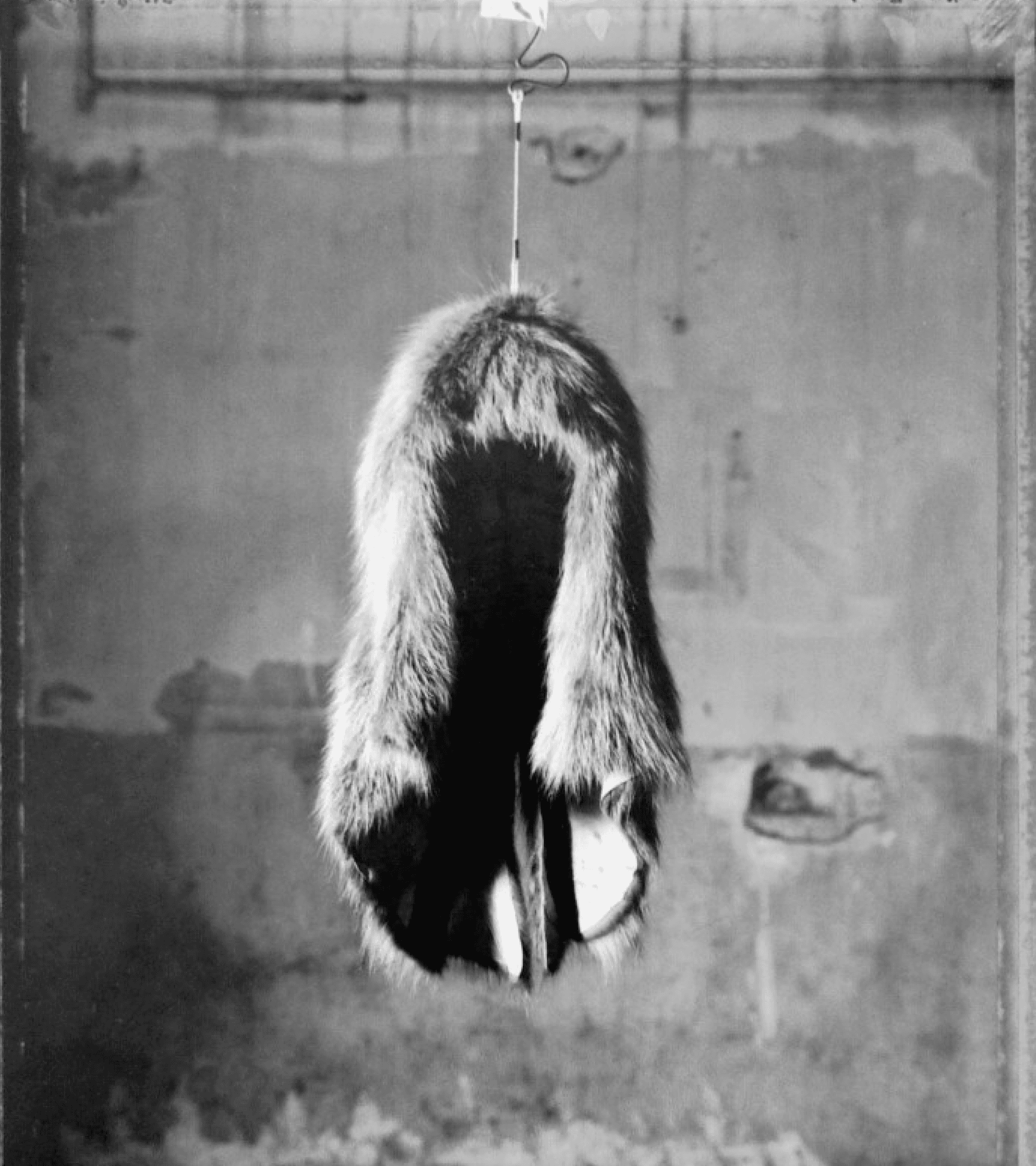

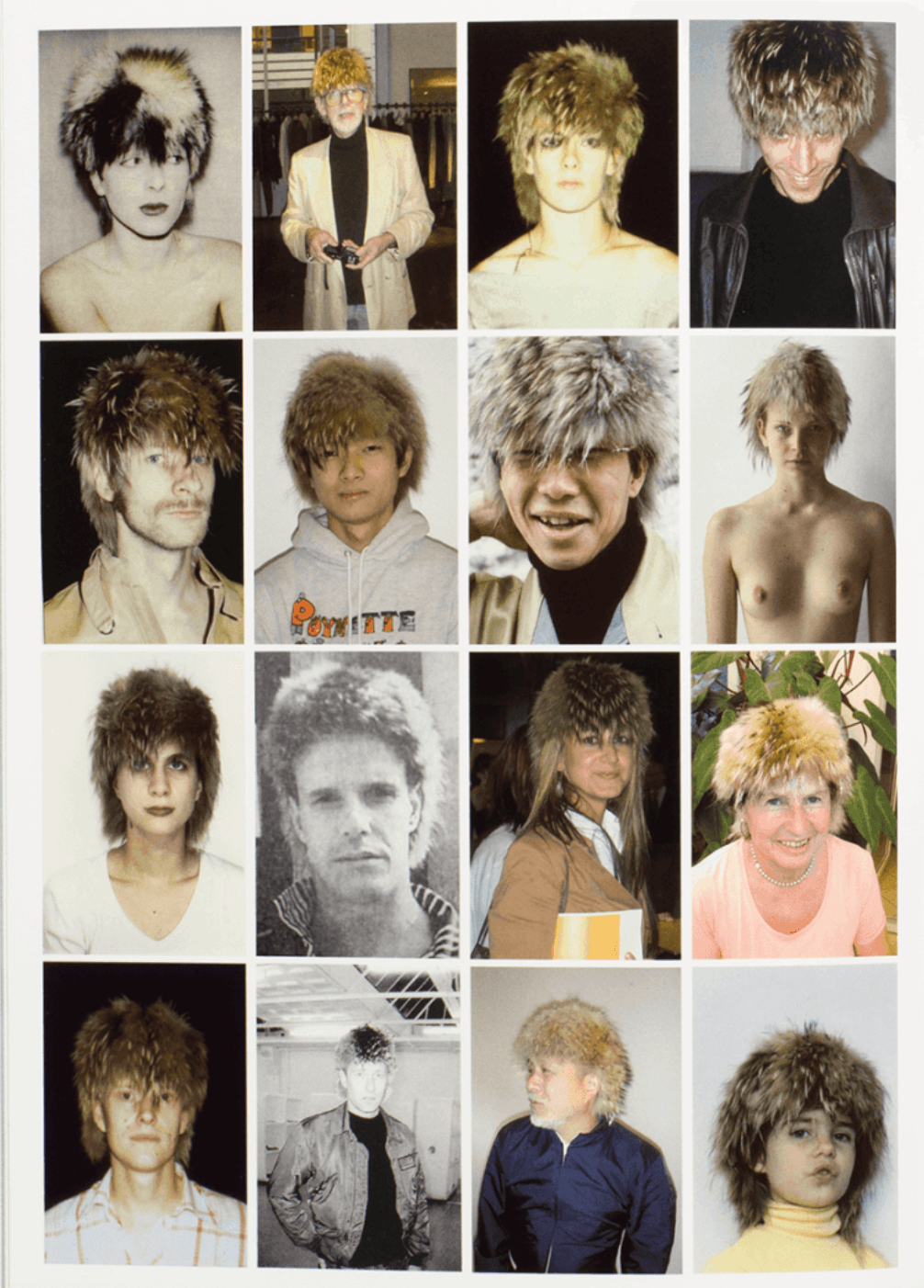

The origin of the fur wigs presented in the Fall/Winter 1997 show can be traced to late 1996, when BLESS, a design practice founded by Desiree Heiss and Ines Kaag, published an advertisement in i-D magazine Autumn 1996 issue. The ad was a paid placement showing a Polaroid of a prototype fur wig made from reclaimed vintage coats, printed with the tagline “Fits every style! Cut & try!” and a contact telephone number.

At the time, BLESS had not yet staged a fashion show. According to later interviews, the designers funded the advertisement using borrowed money. The wig, referred to as “Bless No.00,” was made using fur from vintage coats and cut to resemble a shag hairstyle. The designers have stated that the ad received limited response, with one of the few calls coming from Paris.

The call was made by Patrick Scallon, then part of the communications team at Maison Martin Margiela. He contacted BLESS regarding a potential collaboration for the house’s upcoming Autumn/Winter 1997–98 presentation. The result was a commission to produce a series of wigs for the show using the same type of reclaimed fur and hand-made process shown in the advertisement. This project marked BLESS’s first commercial collaboration. A separate inquiry from the concept store Colette also followed the ad, leading to early retail interest in the wigs.

At the time of the collaboration, Maison Martin Margiela had already established a practice of reworking second-hand and utilitarian materials within a fashion context. Martin Margiela’s interest in wigs and hairpieces as material elements had appeared in earlier collections, and biographical accounts note that he was raised in a household connected to barbering and wig-making. For the 1997 project, Margiela required that all wigs be produced exclusively from second-hand fur garments, sourced from flea markets and dismantled in the Maison’s atelier. The furs were then reconfigured to match hairstyle sketches provided by Margiela, so that the wigs would resemble conventional haircuts rendered in fur.

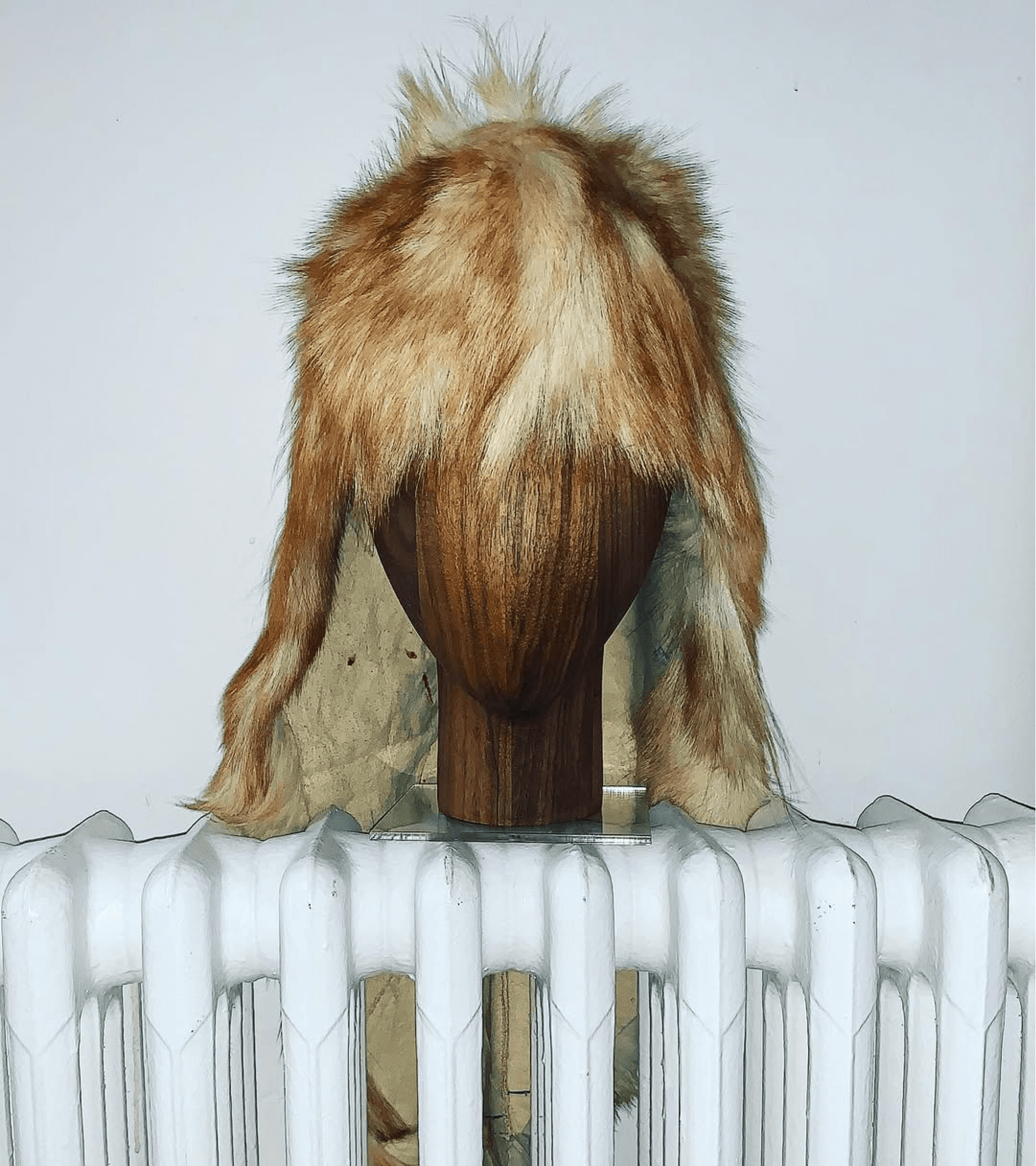

According to institutional records, approximately 30 wigs were produced by BLESS for the show. Heiss and Kaag worked on the pieces from a room within the Maison’s workspace. Each wig was cut and assembled to follow Margiela’s illustrations. Styles included short fringed cuts and longer back sections, using fox, rabbit, or mink fur. Internal tags or rivets bearing the BLESS name were used to mark the wigs as part of the collaboration. The National Gallery of Victoria, which holds one of the original pieces, describes the materials used as vintage fur and notes that the wig was constructed to follow realistic hair patterns based on Margiela’s direction.

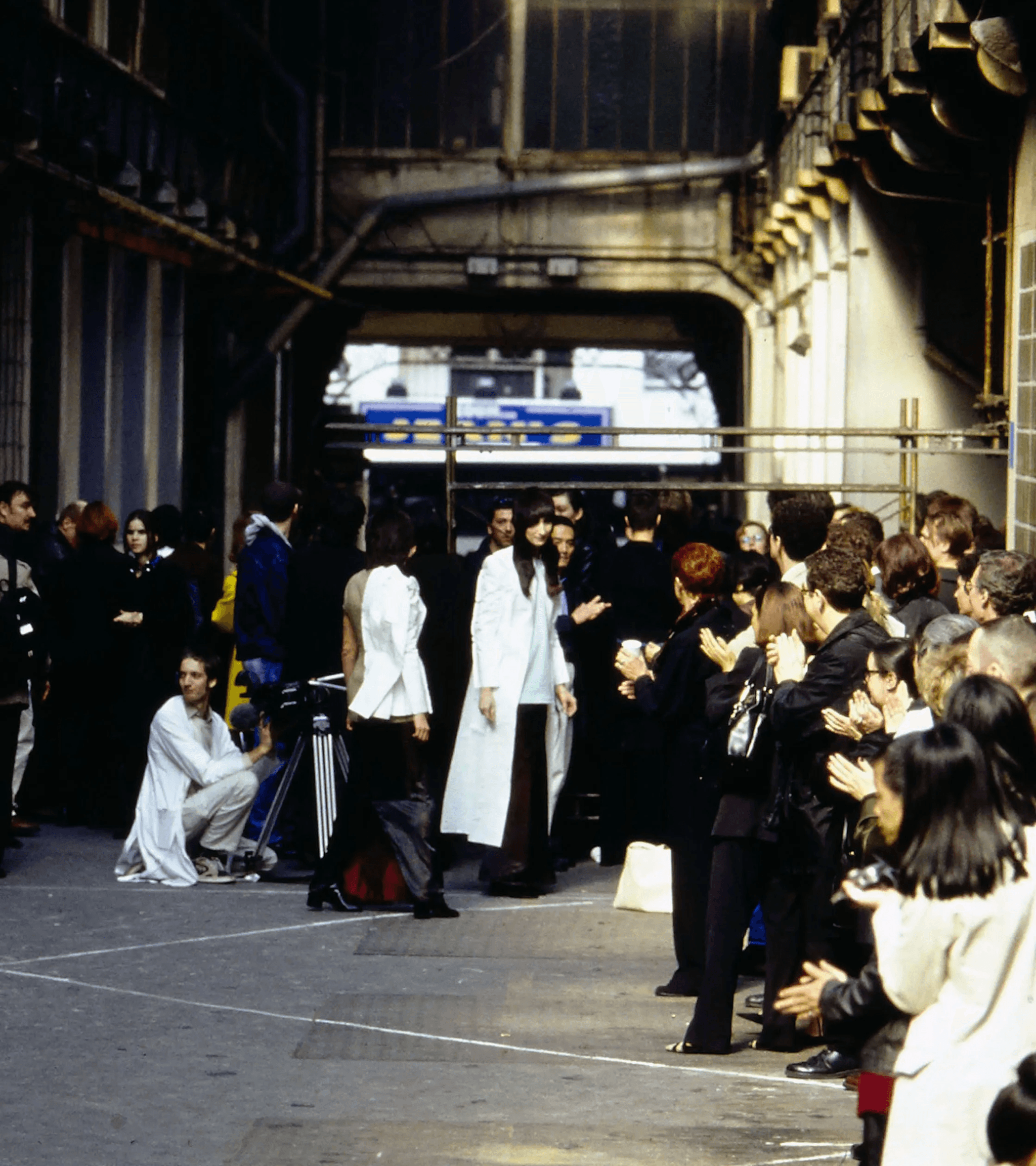

These wigs were presented on every model in the Fall/Winter 1997 show. The presentation took place across several locations around Place de la République in Paris, with guests and models transported between venues by bus. The wigs were paired with garments from the same collection, including pattern paper jackets, visible tailoring structures, and asymmetrical construction, so that the collaboration with BLESS formed part of the collection’s broader material and visual logic.

The use of repurposed fur wigs in a high-fashion runway show attracted significant attention from the fashion press and industry. In later accounts, Margiela’s Fall/Winter 1997 presentation has been cited as one of his most conceptually focused shows of the late 1990s, with the wigs identified as a key element of that season. Contemporary reporting noted the visual uniformity created by placing near-identical fur wigs on every model and described how this choice extended Margiela’s existing work with deconstruction and reconstruction. Vogue later referred to the wigs as “a bit outré” in the context of a collection that also included sleeveless tailored coats and heavy knitwear, and singled out the “fur wigs made from old coats” as a distinctive aspect of the runway.

For BLESS, the collaboration functioned as a first major public appearance. One retrospective account states that, in the winter of 1997–98, all the models in Margiela’s show wore BLESS fur wigs and that this visibility directly increased attention to the studio. The association with Maison Martin Margiela led to interest from retailers including Colette in Paris. In interviews, Ines Kaag has described the period of producing the wigs for the show as an introduction to Margiela’s internal working methods. Because he rarely appeared publicly or spoke to the press at that time, the opportunity to work inside the studio and observe his process has been described by the BLESS founders as formative.

Subsequent criticism has continued to reference the wigs in discussions of the collection. Fashion critic Cathy Horyn has referred to Margiela’s 1997 show as “one of his most powerful,” specifically highlighting the image of models in “shagged wigs cut from old fur coats.” Later profiles have linked this recurring use of hair and wigs to biographical details, noting that Margiela’s father worked as a hairdresser and his mother sold wigs. This has been cited alongside his longstanding use of masks, veils, and other forms of facial covering, which appear throughout his work as strategies to redirect attention from the wearer’s identity to the clothing itself.

BLESS, founded by Desirée Heiss and Ines Kaag in the late 1990s, has been described by its founders as an interdisciplinary studio operating between Paris and Berlin. From its inception, the project has encompassed garments, accessories, furniture, and other objects, organised in numbered “issues” rather than seasonal collections. BLESS has consistently worked with existing materials and everyday objects, reconfiguring them into new forms. Within this framework, the fur wig first advertised in i-D in 1997 is recorded as “BLESS N°00,” and later texts identify the Margiela collaboration as the context in which this piece moved from an experimental object to a widely seen design on the runway.

In museum and exhibition histories, the Margiela x BLESS fur wigs now appear as artifacts representing late-1990s experimental fashion. Institutions such as the National Gallery of Victoria and the Palais Galliera have acquired or exhibited examples of the wigs in surveys of Margiela’s work and of 1997’s fashion output more broadly. These records note their construction from dismantled vintage fur coats, their use on every model in the Fall/Winter 1997 show, and their role within both Margiela’s ongoing investigations into hair and disguise and BLESS’s early development as an interdisciplinary design practice.