DECODING THE ANTWERP SIX AND THE SYSTEM THEY DISRUPTED

1/30/2026

Author: Soukita

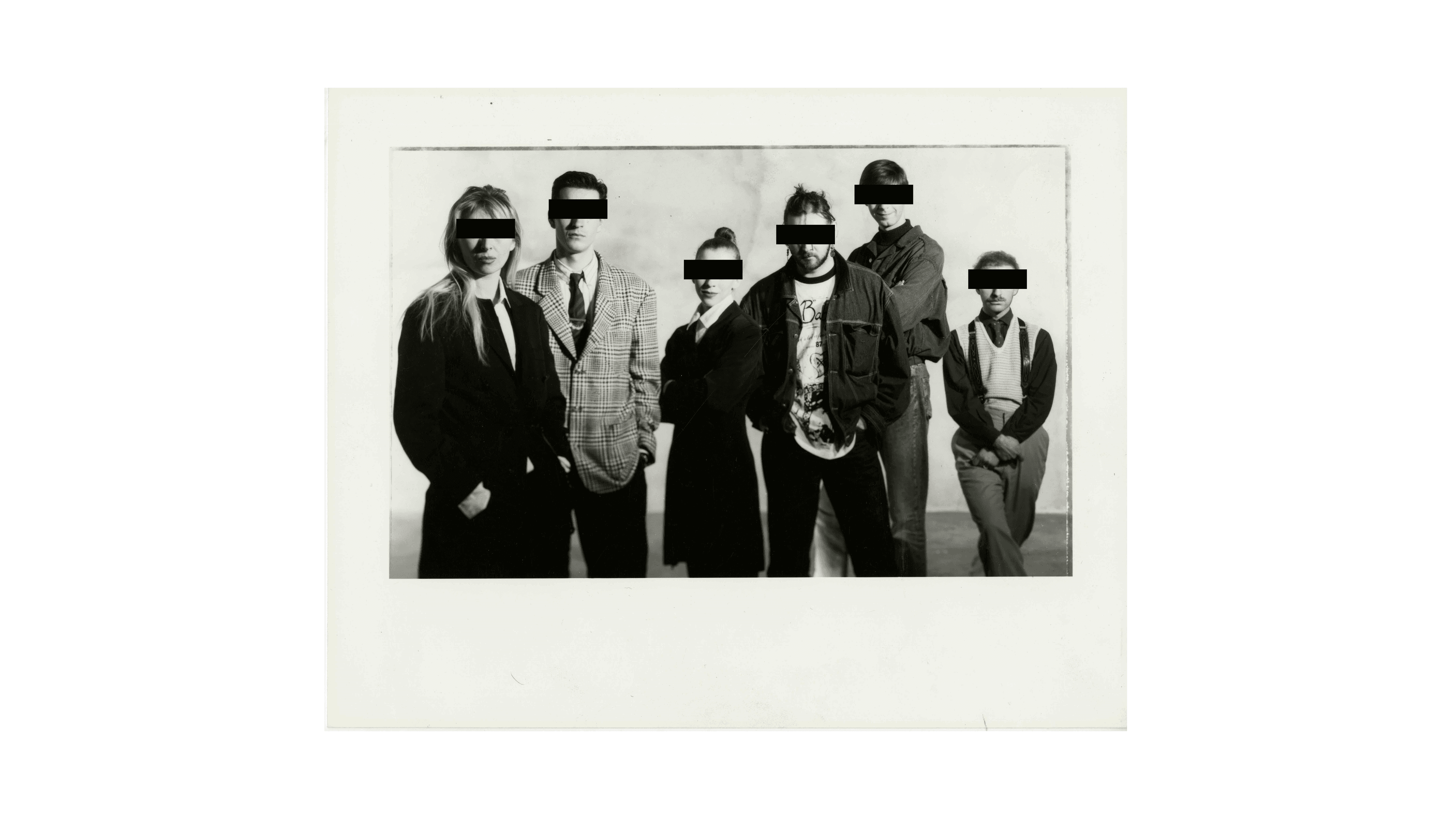

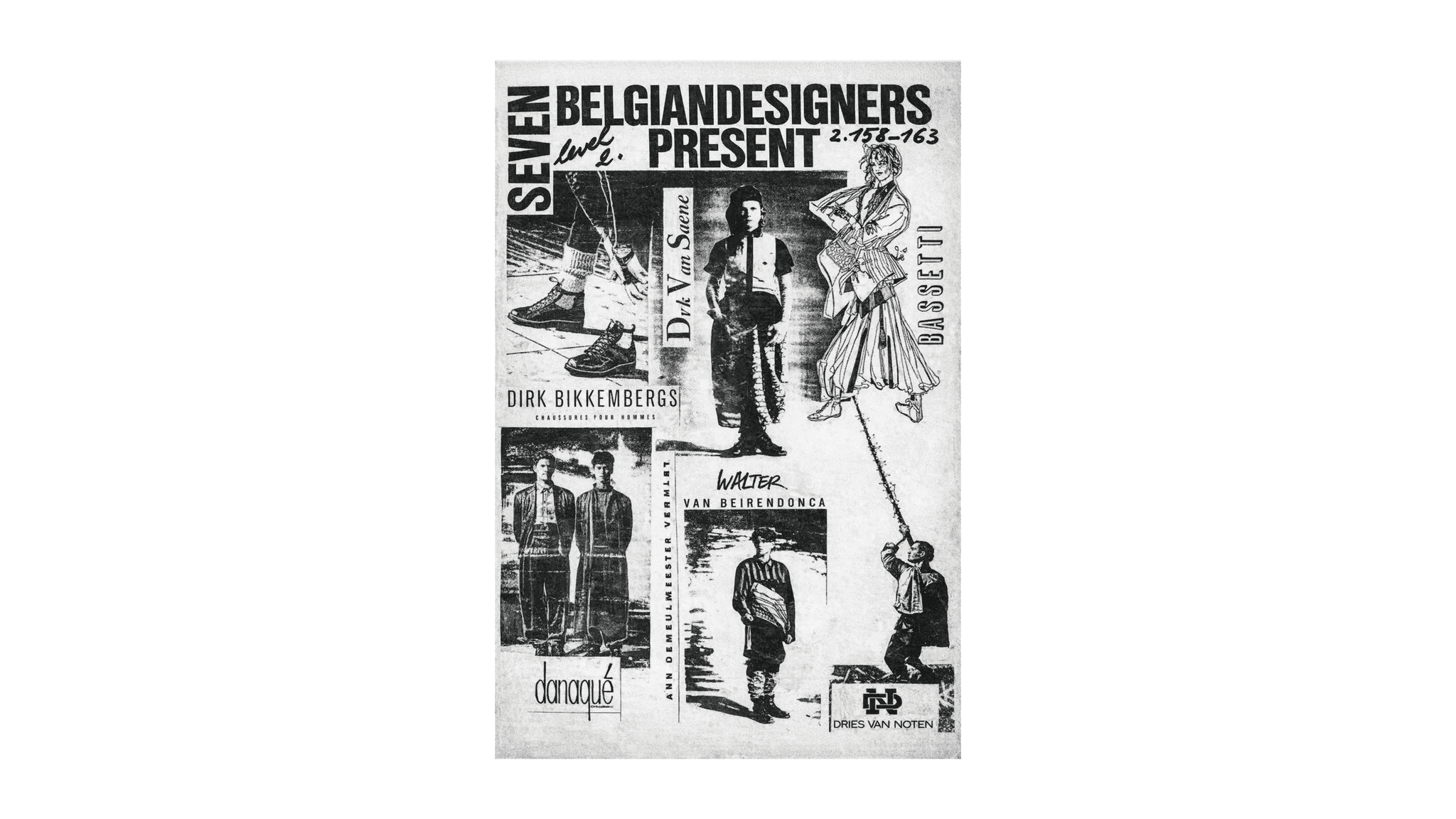

In 1986, six Antwerp graduates drove to London in a rented truck with their collections packed alongside bags filled with hope. Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck, Dirk Van Saene, Dirk Bikkembergs and Marina Yee emerged from Antwerp’s Royal Academy in the early '80s with a singular point to prove: Antwerp was not yet on the map — so they drew it themselves.

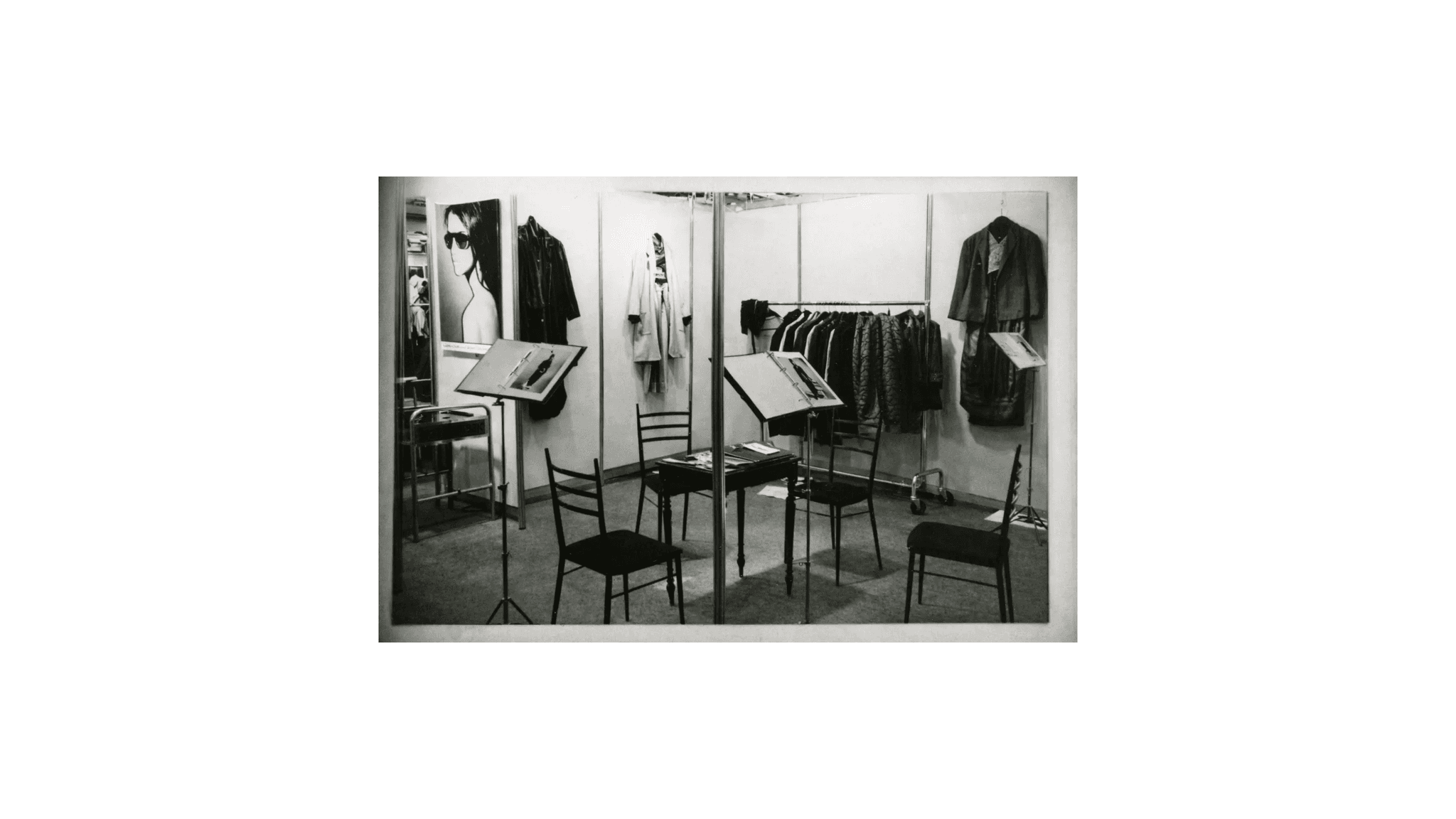

A trade show would become their point of entry. A small room. A chance to be seen without waiting for the right dinner, the right editor or the right invitation.

They were relegated to the top floor. This wasn't the prestige of the penthouse, but the silence of the attic. It was a tactical isolation because the industry does not need to say "no" when it can simply ensure you aren't seen. Downstairs, the money moved in a predictable loop. Upstairs, the Six waited for the few who were willing to break the flow. And then something shifted.

Accounts of that week vary in the details, but the turning point stays consistent: The work was strong enough that once the right eyes made it upstairs, it could not be ignored. One of the most repeated versions of the story is that Barneys New York’s team went up, saw the collections and placed orders. Press followed. And because fashion loves a shortcut, journalists gave it a name that could hold six careers at once: the Antwerp Six.

That week in London became lore, but the lore is not in the romance of the van. It is what the van symbolized: Fashion’s hierarchy is not only maintained by taste. It is maintained by routing. By placement. By access. By who gets put in the room where decisions happen, and who gets politely moved elsewhere.

For decades, the axis ran through Paris, Milan and New York. Houses, retailers and magazines dictated what mattered and where it could come from. Antwerp was not supposed to be a source. Antwerp was supposed to be an asterisk.

The Six did not arrive asking for approval. They arrived with six different design languages and forced the industry to widen its vernacular.

MORE THAN A LOOK, IT WAS A NAME

Ann Demeulemeester proposed a kind of restraint that felt almost confrontational in the glossy, power-shouldered '80s. A poetic severity. Androgynous romance. A monochrome discipline that reads less like minimalism and more like atmosphere. She stepped away from her label in 2013, leaving in a way that felt consistent with her work: direct, private and on her own terms.

Dries Van Noten came with a different instinct: pattern, color, surface and craft. A designer who made richness feel intelligent instead of loud. He stayed independent for decades, then sold a majority stake to Puig in 2018 while retaining a minority stake and continuing in a leadership role, a structural compromise that still kept him inside the room.

Walter Van Beirendonck arrived with flare. Bright, bombastic and provocative, unafraid of humor or confrontation. But part of Walter’s long impact sits beyond the runway. He taught at the Royal Academy for years and later led the fashion department, shaping the school’s next generation of designers and helping Antwerp become more than a one-moment myth. (He stepped down from leading the department in 2022.)

Dirk Bikkembergs pushed masculinity through motion. Sport as design language, athletic codes pulled into fashion without softening them into costume. The label later became closely tied to football culture, and the brand changed hands over time, another reminder that the “outsider” story doesn’t end when the industry finally pays attention.

Dirk Van Saene blurred art and apparel in the literal sense, treating garments like a surface that can hold a hand, a brush — a refusal to look mass-produced. His work has often been discussed through that overlap: fashion as something you build with an artist’s patience rather than a seasonal clock.

And Marina Yee. Often described as elusive. Her practice, especially later, leaned toward repair, reuse and reconstruction long before the industry made those words trend-friendly. She passed away in 2025, and the tributes that followed returned to the same point: She never designed for spectacle. She designed for life, for longevity, for what you could do with what already existed.

Put together, their disruption looks less like a shared style and more like a shared stance: You can succeed without smoothing your edges into something the system already knows how to sell.

THE TRUE EXTENT OF THEIR DISRUPTION

The Antwerp Six didn’t make Paris irrelevant. They made Paris less absolute. They challenged a permission system, not a trend cycle. The old order ran on an assumption: Legitimacy comes from certain cities, certain institutions and certain gatekeepers. Antwerp was not meant to produce names that would reroute buyers and editors. But once Antwerp did, the industry’s senses recalibrated.

After 1986, the hunt for “the next Antwerp” became its own pattern: a new expectation that innovation might come from the periphery, from Tokyo or London or Seoul, from places previously treated as side quests. Not because those places were newly minted, but because the system’s perspective shifted.

And Antwerp itself changed from a backdrop to an engine. The Royal Academy’s fashion department became a reference point, not only because of the Six, but because the school kept producing designers who wouldn’t compress their vision into something easily explained at a showroom.

Then the final irony, the full circle. The outsiders became the institution.

Dries later used his position to argue for reform around the fashion calendar, the kind of move that reads less like a sudden stance and more like a consistent one finally spoken at scale.

Walter’s influence continued through teaching and mentorship, not just collections. Ann exited her house in a way that resisted spectacle. Marina kept working in a register that treated “small” as a choice, not a failure.

These aren’t side details. They’re the point. The disruption wasn’t one season. It was decades of refusing the same pressure in different forms.

THE ARCHIVAL PHASE

Now the story is being archived in the most literal way.

MoMu has announced a major exhibition for 2026 that brings all six narratives together, with Geert Bruloot involved — one of the early supporters who traveled with them to London in 1986. The institution frames the show as overdue for the same reason the story still matters: It’s not only about a moment of discovery, it’s about what happened after, and how six separate trajectories changed what the industry could recognize as “central.”

That is the system they disrupted, in the end. Not a trend system. A permission system.

Fashion renews itself when it makes room for designers who refuse to compress their work into what the market can instantly name.

Sometimes that renewal looks like a new city becoming a reference point. Sometimes it looks like six people on a top floor, forcing the industry to climb.