ALEXANDER MCQUEEN THORN-PRINT FROCK COAT, 1992

11/23/2025

Author: Soukita

On 16 March 1992, at the Central Saint Martins MA graduation show in London, a pink silk frock coat printed with black thorns appeared in Alexander McQueen’s thesis collection, Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims. The show marked the completion of his master’s studies and presented a tightly framed narrative built around Victorian London, sex work, and the 1888 Whitechapel murders attributed to “Jack the Ripper.”

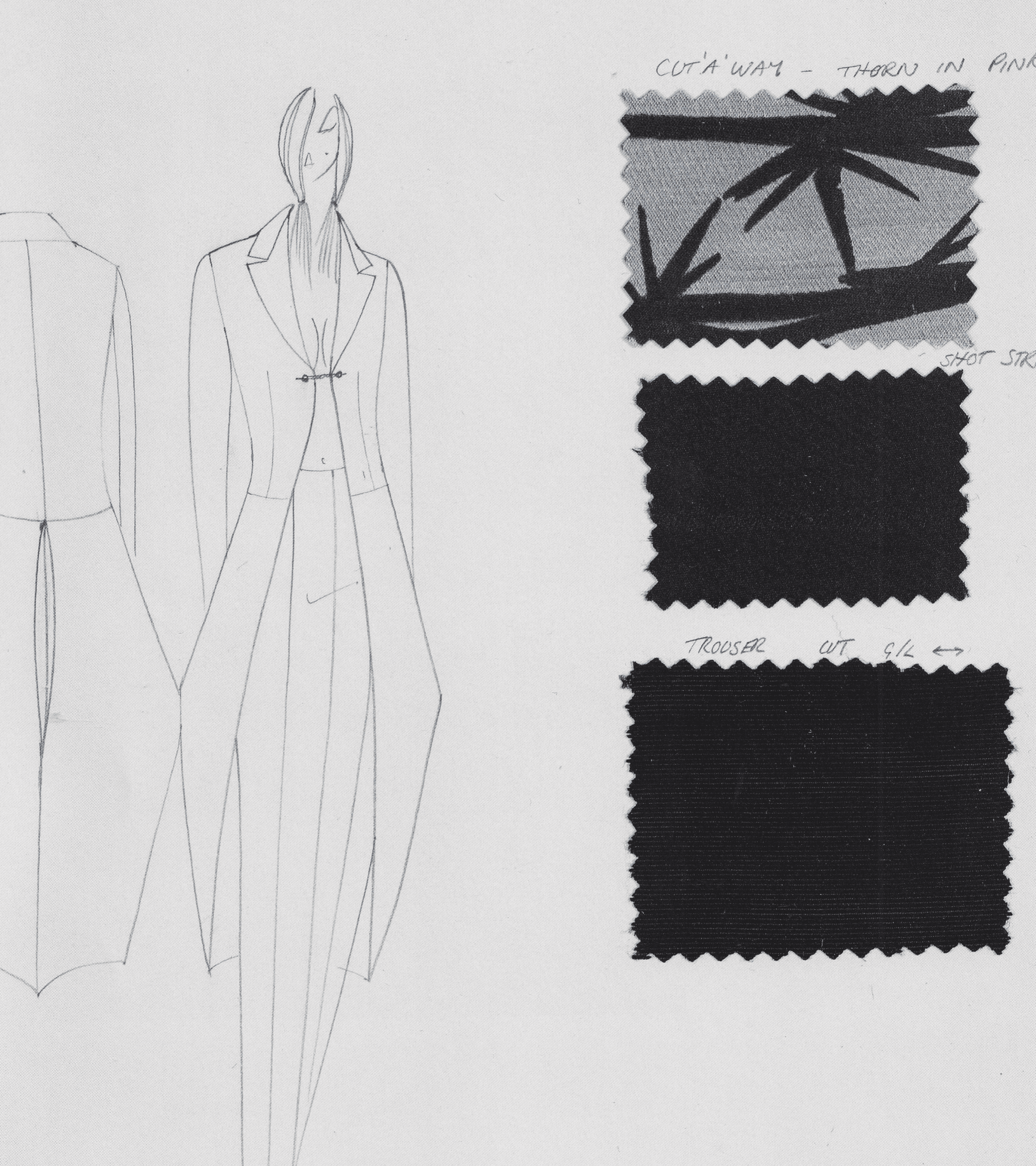

The coat is cut as a frock coat with a narrow, wasp-like waist, high armholes and a three-point folded tail at the back. The outer shell is pink silk satin printed with a black thorn motif developed in collaboration with Simon Ungless, then a fellow student and close collaborator. The print runs across the body and sleeves and covers a structure built from traditional tailoring methods: shaped panels, structured shoulders and a back that holds its form away from the body rather than collapsing when unworn.

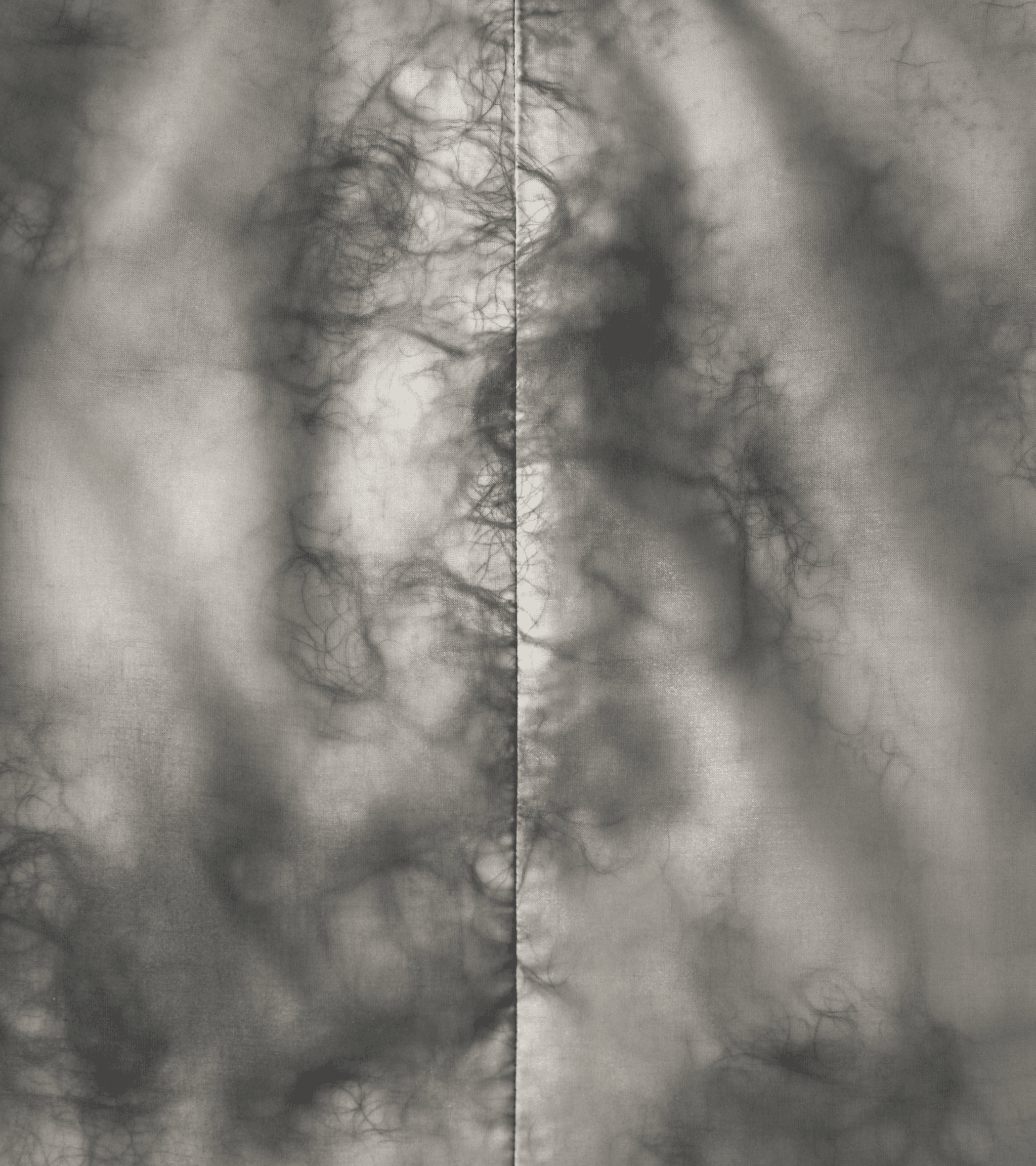

Inside, the lining introduces one of the key elements of the piece. The coat is lined in white silk, stitched into channels that encase human hair. McQueen later stated that this detail was informed by Victorian practices in which prostitutes sold their hair and lovers exchanged locks as tokens, and that in his early collections he used hair as a kind of signature label, enclosed behind transparent or sealed elements. In this coat, the hair sits between body and cloth, not visible from the outside but present as physical material carried by the garment.

The collection title, Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims, points to the Whitechapel murders, but the clothes concentrate on the women and on the environment in which they lived and worked. Surviving descriptions of the show notes record the collection as “a day into eveningwear collection inspired by street walkers.” The palette seen in photographs and preserved garments includes black and deep red, mauve linings associated with mourning, and red linings that suggest exposed flesh. Beads, yarn and paint appear on some pieces to resemble stains or blood. Other garments show burned or abraded edges, so that damage to the fabric becomes part of the design. Tailcoats and evening pieces are cut away to reveal the body, placing exposed skin beside precise cutting.

McQueen’s preparation for the MA collection combined historical research with technical training. Before entering Central Saint Martins he had worked on Savile Row at Anderson & Sheppard and Gieves & Hawkes, and later at theatrical costumiers Berman’s & Nathan. The frock coat reflects this background in its proportions and construction: a tight torso, flared skirt and controlled back volume that correspond to established menswear cutting. At the same time, his written coursework for the degree included a report on genealogy and the Jack the Ripper case, compiled from crime histories and Victorian visual material available in Britain by the early 1990s. The coat brings these strands together in a single object that joins historical subject matter, documentary reference such as hair and thorn imagery, and rigorous tailoring.

The graduation show presented the coat on a small runway inside Central Saint Martins along with other looks from the same collection. Among those present was Isabella Blow, then working as a fashion editor and stylist. Later accounts from McQueen’s circle and from biographies of both figures consistently record that Blow purchased the collection shortly after the show for a single agreed sum. That acquisition included the thorn-printed frock coat. The purchase moved the garments directly from a student presentation into a private archive and marked the beginning of an extended working relationship between Blow and McQueen.

After Blow’s death, many of her McQueen pieces, including the MA collection garments, passed to Daphne Guinness, who has loaned them to major museum exhibitions. The pink thorn-print frock coat is now catalogued as part of McQueen’s 1992 MA collection and as coming from Isabella Blow’s wardrobe. Its key documented facts remain consistent across sources: it originates in Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims, it is constructed from pink silk satin printed with thorns and lined with human hair, and it was worn on the Central Saint Martins runway in March 1992 before entering Blow’s collection.

Viewed within McQueen’s wider body of work, the coat is an early example of several elements that recur throughout his career: tailoring derived from traditional menswear, research into specific historical episodes, use of hair as both material and marker, and a sustained interest in how clothing can register violence, labour and memory. As a single, well-documented thesis garment, it records the point at which these concerns first appear together in his practice and provides a clear link between his student work and the later collections that would establish his international reputation.